Standard read time is about 30 minutes. On most laptops, you can press ctrl + shift + U to read aloud a page.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1: Nostalgic Conservation – How does nostalgia interest people in environmental restoration?

1.1 – Are Memories of Nature Nostalgic? Why?

1.2 – The Nostalgic Impact on Decision Making

Chapter 2: Analysing Nostalgia in Artworks - How Can Nostalgia be Evoked Through Art?

2.1 – The Reputation of Nostalgia in Contemporary Art

2.2 – Analysis of Selected Works

Cultural Nostalgia

Environmental Nostalgia

2.3 – Deploying Artworks to Evoke Environmental Nostalgia

Conclusion

Bibliography

Introduction

In this dissertation, I will be investigating the use of nostalgia in engaging people in our changing environment. I was taught to love nature from an early age and to look out for the little beings around me, I suppose I never really grew out of that. Unfortunately, particularly in recent years, I have begun to notice the seasons blending, becoming more unpredictable, and the wildlife suffering alongside it.

I believe that the best way to engage the public in climate change and species loss is to reignite a love for nature and wildlife, sending messages of hope rather than fear. Society will need to act collectively to mitigate the consequences of climate change and prevent it from becoming even more of a humanitarian issue. Davis, 1979 states that “nostalgia, despite its private, sometimes intensely felt personal character, is a deeply social emotion”. Nostalgia can be an integral part of collective identity, combining shared memories and experiences, and act as a powerful device for motivating action. I aim to find how artworks may evoke this feeling in a way that interests people in environmental restoration.

To answer the question, I divided my work into two main research questions: how does nostalgia interest people in nature? and how can nostalgia be evoked through art? The dissertation has been arranged in such a way that overall understanding and contexts of the topic have been discussed before applying this knowledge to analyse selected artworks. This will allow me to develop a considered and informed analysis that situates the artworks between different viewpoints and arguments. I have gathered research from a broad range of sources, some of which I already knew of due to general interest. I have found reviews to be of particular value while conducting my research. I understood the formatting and viewpoints of a critical analysis of nostalgic art through Paolo Magagnoli’s review of Joachim Koester, critics’ receival of certain works like Arnold-Forster’s book and both the artworks, and through a review by Tom Penalas, found Fred Davis’ 1979 Yearning for Yesterday, a sociology of nostalgia- a book that has been cited by almost every other source in my bibliography. I acknowledge that by not conducting any primary research, I run the risk paraphrasing other’s work, however, I have made sure that I have gathered enough information to create an original and informed analysis of the artworks. I will reaffirm all conclusions made throughout the dissertation at the end, where I will give a final opinion.

~

Despite its vehement dismissal, nostalgia persists within pop culture and political propaganda. For example, Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan created for his presidential election campaign in 2016 and the ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ poster that swept the UK in the 2010s, becoming an internet sensation. Arnold-Forster discusses the recovery of the WWII poster and the repopulation of the propaganda during the 2010-2019 coalition government:

“It worked to keep the peace among a population facing unprecedented financial hardship, imploring them to suck it up and take their complaints elsewhere. Keep Calm and Carry On encouraged the British public to admire a strong, struggling but basically deferent working class, one that knows its place.” (22:00, chapter 10)

The poster didn’t act alone- both labour and conservative parties pushed the narrative that resources were scarce and that spending should be limited, often invoking national memories of wartime rationing. This nostalgia was deployed as a deeply patriotic manoeuvre, reminding Britons of their ‘stiff upper lip’ and a time where their grim endurance paid off for victory. However, articles like Howell, Kitson and Clowney’s 2019, “Environments Past” and Wilson, Hart and Zengel’s “A longing for the natural past” make clear that using nostalgia must carefully avoid glamourising and romanticising the past. This is not only true for the purposes of environmental restoration, but for the broader sense that progress requires a forward-looking approach.

Similar to Syperek’s Hope in Ecology, in Jennifer Landino’s Longing for Wonderland: Nostalgia for Nature in Post-Frontier America, she discusses the nostalgic and outdated foundations holding up the nation’s national parks and the culture built around the closing of the frontier[1]. These foundations are criticised for romanticising the past and some articles, like Wilson, Hart and Zengel (2019) recognise how difficult it is to avoid romanticising the past while feeling the need to preserve it. A common finding throughout my research is the empirical need for caution- nostalgia is an excellent tool for gathering support, interest or motivation for a common goal, but can lead to conservative, even regressive ideologies that ignore society’s cultural and technological advancements.

[1] The ‘frontier’ refers to the line of expansion within 17-19th Century America of owned land encroaching onto the ‘wild’ unclaimed territories. The official closure of this frontier, declared in 1890 by the US Census Bureau would cause a widespread nostalgia for the preservation of ‘wild’ country, a notion that founded and still persists in the nation’s national parks today.

Chapter 1: Nostalgic Conservation - How does nostalgia interest people in environmental restoration?

1.1 - Are Memories of Nature Nostalgic? Why?

One could say that assuming that the feeling of nostalgia can be applied to declining environmental health also assumes that the audience has memories of experiencing these environments before human intervention. While a similar feeling to nostalgia can be occasionally felt without having those experiences personally (Davis,1979), I want to understand why nostalgia is so often used within the context of nature.

There have been countless studies to prove how children’s exposure to nature plays a fundamental role in their development. A particular study by Antink-Meyer, Lorsbach and Brown (2024) found that “given access, children will seek out interactions with biodiversity.” This study alongside findings from Project PigeonWatch in Washington, DC demonstrates how eager children are to interact with and play in nature. PigeonWatch enlisted schoolchildren in inner-city DC to study and record the behaviours of pigeons. They found that the children became more respectful towards the birds and understanding of the complex social lives of another species. “The kids transmute from bird hecklers and sometimes physical abusers to astute observers and advocates of beings whom they had not known how to see or respect.” Haraway (2016) p.24.

The more immersive a memory is to experience, the stronger the feeling of nostalgia becomes. While seeing sentimental objects or photographs evokes a strong emotion, psychoanalysts have found that certain smells and sound in the form of music is particularly resonant. When discussing the attitudes towards and treatments for homesickness in the early 20th century, Arnold-Forster states that homesickness sometimes acts as a homing device, only ceasing when the patient returns home. I believe that returning to a familiar childhood environment, therefore witnessing a memory with all senses, creates a nostalgia far more potent than any other trigger. This works best when the environment is unchanging, and what could be more unchanging than the hill you used to go sledging down? Or the old ash with a rope swing? Or your favourite beach to go rock-pooling? When our natural landscapes change and things are suddenly not how they used to be, a trivial uneasiness absorbs us. Things are automatically worse than what they were and we’re motivated to act on restoring what was made wrong. I imagine this is the main driver for why nostalgia is so powerful at recruiting interest and motivation for environmental conservation.

Much of the ecological restoration that appeals to the right-wing and older generations is in the nostalgic approach of returning nature to the way things were in the ‘good old days’ of their childhood. For many reasons that I discuss in the following chapter, this is not achievable. It is also not the most effective option for the regeneration of natural systems, as it does not take into account the current needs of the ecosystems and planet after centuries of human interference.

As I mentioned in the introduction, nostalgia can be deployed as a very effective tool for a sense of togetherness and need for collective action. Depending on pre-established cultural tendencies, it can be used to make nations and communities grit and bear through tough times, recover from disastrous events or act together towards a common goal. Higgs, et al. (2014) and Howel, Kitson and Clowney (2019) discuss the valuable impact that nostalgia has on the interest and motivation for environmental restoration. The main consensus is that the nostalgia for past landscapes and society’s simple yet harmonious relationship with nature is an effective motivator for change, but the cannot be trusted to dictate decision making due to its overly-conservative nature.

1.2 – The Nostalgic Impact on Decision Making

In this chapter, I will be discussing the implications of a nostalgic outlook on the decisions made within environmental restoration, and the consequence on global ecosystems.

It is well established that nostalgia is one of the leading ways to gain interest in environmental conservation, particularly for older generations and the right wing, especially valuable when environmental concern does not hold a high ranking in right leaning politics. However, Howel, Kitson and Clowney (2019) discuss the importance of recognising when nostalgia drives conservation efforts to become overly focused on replicating past ecosystems. They criticise the nostalgic impact on decision making as it overlooks current issues, aiming to revive or recreate ecosystems that are unachievable or don’t fit into the present ecological needs and global systems.

“It is easy to identify the converse, as well, where forms of nostalgia might be counterproductive to achieving environmental goals by motivating resistance to necessary change: longing for an ocean view without wind turbines, for roofs without solar panels on them or for high power, inefficient, ‘hot rod’ cars. ‘Conservative’ types of nostalgia might likewise engender positive changes by enlisting youthful memories of wooded areas, pristine streams, (organic) family farms and old or historic buildings to protect environmental resources from various destructive forces. Our point in introducing these various scenarios is that nostalgia is frequently unrealistic.” (p 313)

They remind us that nostalgia is particularly useful for enlisting environmental support and motivation for ecological restoration, but to remember to envision an outcome that recognises our technological advances and includes space for modern society. Some examples of restorative-focused conservation efforts include the gradual eradication of rats from New Zeeland. Rats were unintentionally introduced to the island with the European traders of the 18th and 19th Century, the stowaways would populate the island, famous for its lack of predators, and eradicate a large proportion of the unsuspecting species living there. According to Brooke (2007) ship rats were accidentally introduced to Big South Cape Island in 1964, and “quickly eliminated five types of native bird, one bat species, and a large flightless weevil”. Efforts have since begun to get rid of rats entirely, working through the small peripheral islands first, and the native species and ecosystems have benefited greatly.

Another celebrated example is the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park. In 1995, a group of 41 wolves were introduced to the park after almost 100 years of their absence. It was understood that they were a keystone species[2], vital to the balance of the elk populations, which exploded in numbers, eating dramatically more vegetation, therefore impacting the balance of a plethora of other species and systems. With the reintroduction of the wolves came the reversal of these issues, and Yellowstone’s ecosystems are flourishing once more.

Some more extreme environmentalists are suggesting that wolves should also be reintroduced to Britain, claiming the same effects would ensue. While our rivers and ecosystems do suffer as a result of the overpopulation of deer, Yellowstone National Park is almost two times the size of our largest national park, covering almost 9,000 square kilometers versus our Cairngorms at 4,528, and even a small population of wolves need a significantly large area of land to thrive without posing a risk to humans and our livestock. In recent news, two lynx have been captured after their illegal release in the Scottish Highlands. While their behaviour is vastly different, having no records of ever attacking a human, they would function in a similar way to the wolves in reducing herbivore populations and still pose a risk to livestock. In a BBC article on the matter, the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS) states how irresponsible the release was, without proper acclimation of the lynxes, it is likely that they would have perished to disease or other environmental change. It is also to be noted that thorough consideration needs to be given to any introduction of a new species, even if they have previously lived in the area. Other large animals used to live in the UK such as bears and European bison. Even with consideration to their ecological benefits, it is completely inappropriate to assume these species can return to Britain due to the amount of space the animals require and their interference with communities and their sources of revenue. It is clear that another approach needs to be made to combat deer populations in the UK, one that is more sporadic, organic and achievable than hunting and culling but doesn’t rely on apex predators that could endanger our own food supplies and livelihoods.

Environments Past also discusses the differing outcomes of nostalgia on right and left-leaning policies. It found that while conservatives are more motivated by a desire to preserve the good things from the past, leftists are more strongly motivated by a desire to improve the world for the future. This type of nostalgia can result in a more general desire for a utopian society that lives harmoniously with our environment, for example back-to-the-land movements and solarpunk[3] aesthetics. Projects that focus on what our current global systems need rather than attempting to return the landscape to its idyllic past may seem less appealing to some, the world has changed much since the impact of humanity and modern ecological plans may not be as obviously beneficial without explanation.

[2] A keystone species is a species that is recognized to have a profound impact on the functioning of an entire ecosystem

[3] The BBC defines solarpunk as “an art movement which broadly envisions how the future might look if we lived in harmony with nature in a sustainable and egalitarian world”

2.1 – The Reputation of Nostalgia in Contemporary Art

Before analysing the selected artworks, it is important to first understand the position and contexts of nostalgia in general society, politics and the world of contemporary art. In this chapter, I aim to outline the reputation of nostalgia in general and within the world of contemporary art. Comparing the views of Fred Davis and Agnes Arnold-Forster and their experiences within the ‘Nostalgia Waves’ of the 1970s and the 2020s respectively, I have explored research made through different time periods. These works situate nostalgia within the context of 70s society and the politics, recessions, wars and events throughout history. The article Critical Nostalgia in the Art of Joachim Koester by Paolo Magagnoli (2011) discusses the role of nostalgia within the work of Joachim Koester and the different ways nostalgia is utilised and criticised in the world of contemporary art. Combining the research of these sources will enable understanding of the complete contexts and reputations of nostalgia throughout the ages and how this impacts the popular view today.

Along with Davis (1979) and many other research sources I have investigated, Magagnoli (2011) and Arnold-Forster (2024) discuss the widespread dismissal of nostalgia amongst critics. This dismissal is due to many reasons- the view that nostalgia is merely an adulterated view of the past that forgets many important details, conservative connotations from right wing politicians using “nostalgic appeals to the ‘glorious’ pasts of their nations in political propaganda”(Magagnoli, p. 101), and the impression that focusing on the past is generally unnecessary if for reasons other than acting in the present and future. Arnold-Forster argues that one of the main reasons for its dismissal is the elitist view that nostalgia is reserved for the poorly educated, the right wing, the lower class and the war-torn immigrant. Even after centuries of research and cultural shifts “it remains, strangely, a kind of diagnosis, an explanation for what the critic sees as wayward or irrational acts” (05:26, chapter 10).

As addressed in the introduction, despite its supposed inferiority, nostalgia persists within popular culture, and some elements may be deemed acceptable by the contemporary art scene. The revival of film photography in the modern age is one such nostalgia that the art world is not immune to. Rooney (2017) discusses the way that turning back to film over digital is a way that millennials are reconnecting with their childhoods. He states that the combination of the slow, methodical, tactile process, the imperfections that result from human and chemical error, and the raw authenticity compared to digital’s precise perfection contribute to its popularity. He compares the uncontrolled natural element to film development to the way that the Dadaist movement ‘used chance as a method of artistic expression’.

The general conclusion I have gathered from this research is that while nostalgia can dangerously romanticise the past and is viewed warily by critics, it ultimately acts as a powerful unifier to bring together nations and communities into acting towards a common goal. Within general society, nostalgia often dictates the trends in pop culture and these trends can occasionally influence the modern art world.

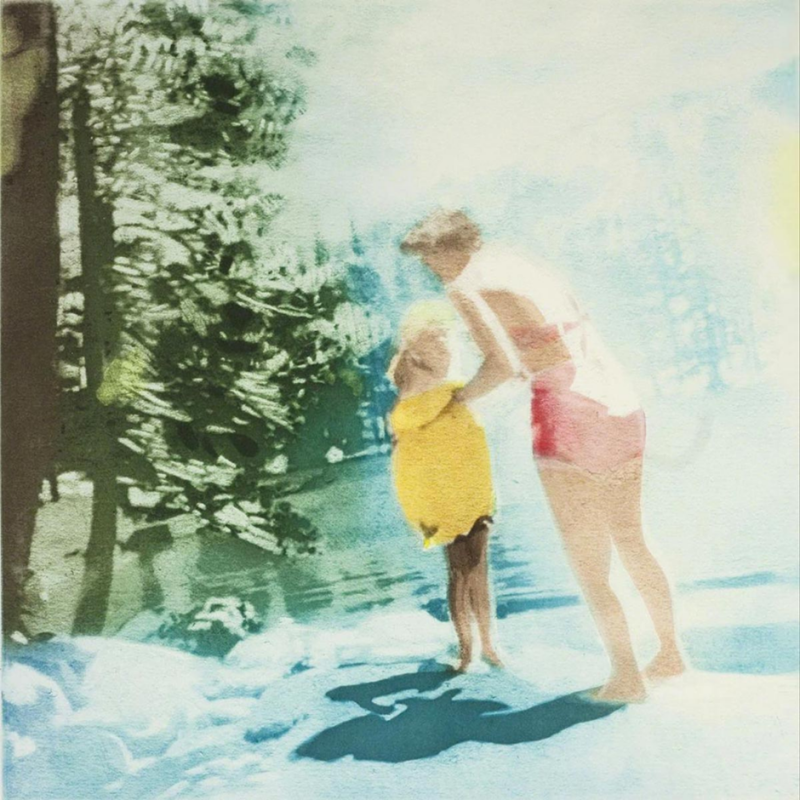

Figure 1: Isca Greenfield-Sanders, Pikes Peak (c.2012), watercolour painting.

Video – Justin Kaminuma, Who will you think of, Video montage, 2024 (audio- Alex G, mis, video source- @digitalvideosss on Instagram) Available at: https://www.instagram.com/reel/DA6IAnvRH4H/ slight flash warning

Cultural Nostalgia

I will be comparing two different artworks that both convey a strong feeling of nostalgia to the viewer. Pikes Peak by Isca Greenfield-Sanders (figure 1) is a watercolour painting of a maternal figure and a young girl drying off by an alpine lake. Who will you think of by Justin Kaminuma is a sepia video montage that includes brief clips of friendly figures in natural and urban settings, paired with homely window views and pets in gardens and running through waves. Put into the context of the artists’ portfolios of works, different atmospheres surround each of the pieces. Yet, I believe that a frame from Kaminuma’s videos (when painted in a similar style) would not feel alien amongst Greenfield-Sander’s paintings; likewise, a scene painted by Greenfield-Sanders would assimilate well into Kaminuma’s montages. Both artworks feature scenes and figures that feel familiar even when the viewer has never seen them before. The familiarity comes from situating one’s own personal memories within the activities and places shown. In this chapter, I aim to relate my research to these works, discussing the different arguments made and situating the pieces between them.

According to Magagnoli, Joachim Koester’s work is nostalgic because it replicates, revisits, reenacts or recreates. Kaminuma’s montages use found footage recorded on old digital camcorders, reenacting nostalgic memories of childhood for the young millennial/old gen-z audience. Greenfield-Sander’s paintings recreate film slides from the 1950s and 60s, ‘elevating them into larger, more monumental oil paintings’, as she said in the interview with Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art.

Arnold-Forster states that nostalgia often distorts our view of the past, romanticising it to an occasionally dangerous extent. Both of the artworks distort images (or videos) physically, by evolving film slides into paintings and by applying filters and effects to videos. They also distort our views of the past- Greenfield-Sanders creates colourful paintings with a peaceful tone only of a specific demographic (the outdoorsy white American family). This is particularly the mid-century American suburbia that nostalgics want to remember, one without the racial and sexual oppression or civil rights movements, only what would be remembered in a family photo album. While Kaminuma includes more of a variety of shots in his montage, it is still filtering our perception of the past, encouraging us to remember specific personal memories. Another distortion is the removal of the shots from their original contexts of time and as family photos and personal memories, by displaying intimate moments anonymously, to an audience who never knew the photographers.

In Yearning for Yesterday, Fred Davis discusses how nostalgia is one of the many psychological resources that we deploy to defend ourselves against the threat of change. Through Kaminuma’s video and his audience, I can assume that the threat is the distress of losing elements of childhood as people grow older or transition into adult life. A nostalgic comfort from childhood for anyone is a reminder of the way that it has been captured- in the form of souvenirs, diaries, cassette playlists, film photographs, CDs and DVDs, or early digital cameras, in the following years, smartphones will become nostalgic for the youth of today. In the introduction of her book, Arnold-Forster describes nostalgia as a tool that “raises self-esteem and enhances optimism for the future”, a person that is suffering from existentialism or an aging, changing life can find solace in nostalgia, it helps to ground the sense of self and reaffirm social connections to those close to them.

In terms of Pikes Peak, nostalgia could be a comfort to the political unease America has felt over the past 30 years. 50s suburbia represents the pinnacle of the American dream and is often a golden age crutch that the right wing cling to. This era boasts the height of capitalistic comfort living and a simple, rigid set of ideals kept people in their place. Just as Davis says: “nostalgia tells us more about present moods than about past realities”. But does Greenfield-Sanders really idealise the strict stereotypes and expectations of the 50s? Many women and people of colour enjoy dressing and decorating their homes with 50s aesthetics, but that is not to say that they wish to relive that moment in time. Most people who adopt historical hobbies or fashion of any era come to acknowledge that they much prefer the present day and are grateful for the progression of rights and technologies, this appreciation seems to grow the more historical context the person learns.

Similar to this concept, Magagnoli believes that “along with a conservative, reactionary nostalgia, there can be a critical and progressive one”. His review of the series of works by Joachim Koester discusses the ways in which the artist uses elements from the past to relay specific nostalgia for certain elements of society or culture where Koester believes are better than the current system. With Kaminuma’s montage, it’s clear that there is very little, if any social commentary intended. The artwork is created with the objective to incite a contemplative state in the viewer, helping them reflect on their own personal experiences. There is also little more inference to be made from Greenfield-Sander’s painting, perhaps that the type of time that we spend outdoors and in nature has changed. The peacefulness of her works is one of the most notable features, maybe our environment has changed to the extent that we now have to make an active choice to engage with nature, there are no longer such casual interactions. I acknowledge that this is my own inference on her work, she has made no such comment, and that I may be informed by a nostalgia that Magagnoli and other critics are cautious of.

Environmental Nostalgia

The selective approach to nostalgia mentioned by Magagnoli is shared by Howel, Kitson and Clowney (2019). They discuss how it is important to use nostalgia as a motivator to work towards a more harmonious relationship between society and the environment, rather than romanticising and replicating ecosystems and primitive practices of the past. Environments Past also addresses how fundamental nostalgia is in gathering motivation and interest in environmental restoration. Does the nostalgia present in Pikes Peak and who will you think of incite any restorative motivation? While the painting is of a further past than the montage, I would argue that they both incite a similar level of appreciation and interest in the environment. Greenfield-Sander’s painting acts like a direct time capsule of a past landscape. The picture-perfect bubble of the 50s family enjoying a pristine forested lake is a past landscape and experience that most would love to preserve or recreate in some way. The environmental shots within Kaminuma’s video are slightly less potent, as they are juxtaposed with continued domestic and urban clips. One could argue that this shows an appreciation for both the natural and human environments, however, and places our impact on the world within the beauty of our natural planet; a virtue sought by Howel, Kitson and Clowney. While nostalgia for past landscapes inspires love and motivation, for some it could only bring a bittersweet sadness for a land that they cannot possibly return to.

Within the work of Arnold-Forster, she discusses the specific nostalgia for the homeland felt by the immigrant, forced out of their home through political or financial hardship or fleeing from war. For some, they are able to return through video calls to family members, or for short visits if they are lucky. For others, when they are already excluded within their new community, they cannot return home for lack of financial or logistical means. Those that suffer the most cannot return home because it doesn’t exist anymore, destroyed through natural disaster, through conflict, or just that the area has continued to change during their absence. “They longed for somewhere, but that somewhere was a place preserved in a particular moment in history”(Chapter 3, 47:00). She argues that the mental illnesses these migrants experience[4], such as depression, anxiety, or PTSD, are symptoms of an acute homesickness and nostalgia for their homeland. Nostalgia has come so far from its origin that it is no longer considered as a possible illness or cause for sickness, it is now simply an emotion.

I believe that this acute nostalgia for a lost beloved landscape can also be applied to the landscapes lost due to climate change and environmental degradation. Within my lifetime, I have witnessed significant changes to my local environment and that of my family. Excluding any national or global ecosystem change like species populations or weather patterns, multiple greenfield sites of my village and surrounding area have turned into housing estates (some of which were floodplains), storms have cut destroyed cliff paths down to beaches that may no longer exist, and seemingly mountainous sand dunes reduced from rolling hills to slumps to flat beach. I propose that Greenfield-Sander’s painting and Kaminuma’s montage contain past landscapes that create another type of nostalgia. I wonder if the lush forest pictured in Pikes Peak has survived the wildfires that spread further each year, or if the electricity pylons between the trees of who will you think of have withstood the prevailing and intensifying tropical storms? These artworks represent a freezeframe in time, a landscape captured and preserved, like a memory, despite its rapidly changing world.

Within this context, Albrecht (2007) introduces the idea of solastalgia- the distress caused by environmental change impacting people within their home environment. He argues that there is a distinct link between the increase in environmental distress syndromes and the increase in human distress syndromes. Worldwide, people’s sense of place and identity is becoming challenged by the ever-pressing stress of our changing environment. A common solution to existential stress is nostalgia, maybe artworks of past landscapes and environments will become more popular.

Wharldall (2024) establishes the idea of multispecies mourning, an acknowledgement and grief for the non-human species lost to environmental degradation. Though intensely difficult for any individual, grief for loved family and friends has been a part of every culture since the conception of society. Processes of grief differ greatly depending on the person, but psychology and society have aids and suggestions to try and navigate the pain. There has been no need for grief processes for landscapes, ecosystems or species before now. She suggests that nostalgia and art therapy will play a key role in the recognition of this grief, and while I hope it never needs to reach this extent, I know that histories told through art and science combined will play a key part in this.

To conclude, Greenfield-Sander’s painting may romanticise the American 1950s suburbia, but acts as a small rose-tinted window to the long-gone time that a family enjoyed a trip to Pikes Peak in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. Kaminuma’s video calls to the audience that is afraid to lose their childhood, and serves as a reference to a generationally specific experience of the natural-urban landscapes. The artworks I have selected may not intentionally be related to environmental nostalgia, but they undoubtedly tell stories of nostalgia using past landscapes. The interpretations of these works by others may be vastly different, however to me, they represent snapshots of time enjoyed in the environment- both urban and natural. The works give agency to anonymous clips and photos of the past, immortalising the landscapes in their peacefully nostalgic snow-globe-like scenes.

[4] Migrants in the UK are up to 5 times more likely to have mental health needs than the rest of the population

2.3 – Deploying Artworks to Evoke Environmental Nostalgia

The selected artworks may not have been created to convey the specific type of nostalgia I have been discussing and, despite their apparent effect on the audience, they may not have been created with nostalgia in mind at all. Likewise, not every viewer of these pieces may experience nostalgia when viewing them. One may look at Greenfield-Sander’s painting and only see an elegant landscape painting of a lakeside, or only think of where the shots could be taken or how they were stitched together when watching Kaminuma’s montage. I chose these works because they are clearly nostalgic to me, though they might not be to others.

This encourages the question- what kind of artwork is best for evoking environmental nostalgia? Because people and their reactions differ so intensely, there is likely no sure way to create an artwork that evokes a pinpoint specific emotional response in all its viewers. Even the simple poster slogan “Keep Calm and Carry On” could incite a whole range of feelings, ranging from intense national pride and patriotism to begrudging endurance of unfair or unsuitable conditions. In many cases, the way a work is received is often more impactful than the narrative the artist initially set out to make.

To appeal to the audience, artists may use anthropomorphic techniques or build on existing anthropomorphised species. The logo for the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) (figure 5) was created by Sir Peter Scott in 1961, inspired by Chi-Chi, a giant panda that arrived at London Zoo the same year. At the time, Scott said “We wanted an animal that is beautiful, endangered, and loved by many people in the world for its appealing qualities.”[5] The logo still stands as an iconic representation of the leading worldwide conservation fund.

Figure 2: Original sketches by British environmentalist and artist Gerald Watterson of the WWF panda icon alongside evolution of the logo, courtesy of WWF website: https://wwfbrand.panda.org/logo/

Alongside its loveable personality, the panda is well known for its distinct difficulty to keep from extinction. The panda may have been the best choice for the face of wildlife conservation- as one of the most protected species, in 2018 it was estimated that around USD$225 million is spent on its conservation annually (Cell Press, 2018). It is also estimated the pandas generate around 10 to 27 times that amount in income. While anthropomorphism of endangered species can evidently profit monetarily and ecologically, it is unfairly favoured to the ‘more loveable’ species. For instance, the National History Museum has a relatively low amount of invertebrates on display, despite making up 90% of all fauna. “Anthropomorphism as a strategy risks prioritizing those animals that are more readily anthropomorphized” Syperek (2020).

As the panda is a significant cultural icon in China, the English Oak may be considered as significant to the UK, perhaps in a different way. Used through countless legends and stories, it has come to represent strength and a national symbol for resiliency. While the oak is in no way threatened, many individual trees have proven worthy of protest when they are unexpectedly or plan to be felled. For example, the story of the ‘Sycamore Gap’. When a 200-year-old sycamore tree was felled from its proud position by Hadrian’s wall in 2023, it made national news and sparked public action in the form of many new projects to somehow restore what had been lost. The tree had been a landmark to visit, witnessing proposals and the scattering of ashes (Robinson, 2024). While the stump has grown multiple shoots, showing promise that the sycamore will regrow, it could take another 200 years for the tree to return to its former glory.

To conclude, using anthropomorphism and cultural relevance to incite public interest in endangered species proves successful. The most effective ways to represent such species is through consistent iconography. The sycamore gap tree and the WWF logo both stood out as bold, recognisable icons that consistently represented their purpose for generations. This is something that builds familiarity and trust with the public, earning their attention when such icons are threatened.

[5] The panda was also chosen because it was black and white, so reducing printing costs

Conclusion

When I started this dissertation, I had thought little of nostalgia as much more than a strong emotion. I hadn’t considered that it could be used to critique current systems or as right wing propaganda.

To bring my research to a close, nostalgia is an extremely complex emotion. In some cases, it incites a bittersweet feeling that reminds us of our loved ones and reaffirms our sense of self and place within our community. It can help us process grief and inspire us to take action to restore elements of the past. In other cases, it is still the illness it was once conceived as, with symptoms of bouts of homesickness and grief that result in mental and physical illnesses.

Nostalgia is very useful but needs to be closely monitored and applied specifically to ensure that it has the ‘correct’ effect on people. They need to understand that nostalgia has a tendency to romanticise the past and gloss over primitive systems with a rose-tinted lens. Specific parts of a time need to be highlighted, picked out to have the maximum positive impact for the environment and for progression as a society.

Overall, it’s important to interest people in nature, make them feel nostalgia for the harmony of the past environmental systems and abundance of species, but understand not to try to directly recreate these specific ecosystems as they are no longer viable/ easiest option/ most effective at restoring global systems.

Bibliography

Books

Arnold-Forster, A. (2024) Nostalgia: A History of a Dangerous Emotion (Audiobook). Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Audible-Nostalgia-History-Dangerous-Emotion/dp/B0CMY2KWXG?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr= (Accessed: 17 December 2024).

Davis, F. (1979) Yearning for Yesterday: a Sociology of Nostalgia, New York: The Free Press.

Harraway, D. (2016) Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, London: Duke University Press.

Blogs

DECOY (2008) ‘Project Pigeon Watch’, Blogger, 24 March. Available at: https://projectpigeonwatch.blogspot.com/

Magazine Articles

Rooney, C. (2017) ‘The Analogue Revival: Memory, Nostalgia and Error in Contemporary Film Photography’, Glossi Mag, 31 May. Available at: https://glossimag.com/analogue-revival-memory-nostalgia-error-contemporary-film-photography/

(2022) ‘What Is Nostalgic Art’, Masterworks, 8 December. Available at: https://insights.masterworks.com/art/irl/what-is-nostalgic-art/#:~:text=Blending%20high%20and%20low%20influences%2C%20nostalgic%20art%20is,childhood%20memories%20and%20collective%20nostalgic%20memory%20for%20inspiration.

Journal Articles

Albrecht, G. (2007) ‘Solastalgia: The Distressed Caused by Environmental Change’, Australasian Psychiatry, 15(1), pp. S95-S98.

Antink-Meyer, A., Lorsbach, A.W. and Brown, R.A. (2024) ‘Children’s nature play: access to the outdoors and interactions with biodiversity’, Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, pp. 1–17. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2024.2420316

Howell, J.P., Kitson, J., Clowney, D. (2019) ‘Environments Past: Nostalgia in Environmental Policy and Governance’, Sage Publications, 28(3), pp. 305-324.

Higgs, E. et al. (2014) ‘The changing role of history in restoration ecology’, The Ecological Society of America, 12(9), pp. 499-506.

Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T. (2016) ‘Past Forward: Nostalgia as a Motivational Force’ Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(5), pp. 319-321.

Syperek, P. (2020) ‘Hope in the Archive: Indexing the Natural History Museum's Ecologies of Display’, Journal or Curatorial Studies, 9(2), pp. 206-229.

Wharldall, B. (2024) "Toward Multispecies Mourning: Imagining an Art Therapy for Ecological Grief", Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 41(3), pp. 128–134.

Wilson, K.G., Hart, J.L., Zengel, B. (2019) 'A longing for the natural past: unexplored benefits and impacts of a nostalgic approach toward restoration in ecology', Society for Ecological Restoration, 27(5). Available at: doi: 10.1111/rec.12985

News Articles

Scott, K. (2025) ‘Lynx captured after illegal release in Highlands’, BBC News, 8 January. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cj6z61ylj40o (Accessed: 12 January 2025)

Smith, N. (2021) ‘What is solarpunk and can it help save the planet?’, BBC News, 3 August. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-57761297 (Accessed: 29 December 2024)

(2023) ‘Next steps for the Sycamore Gap Tree’, National Trust, 14 September. Available at: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/north-east/hadrians-wall-and-housesteads-fort/next-steps-for-the-sycamore-gap-tree (Accessed: 28 December 2024)

Robinson, C. (2024) ‘Sycamore Gap tree: The story so far’, BBC News, 1 August. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-tyne-66994729 (Accessed: 28 December 2024)

(2022) ‘Peterborough: Final parts of 600-year-old Bretton oak tree felled’, BBC News, 30 June. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cambridgeshire-61997139 (Accessed: 3 January 2025)

(2020) ‘Ancient tree being cut down in Northamptonshire despite campaign’, BBC News, 4 May. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-northamptonshire-52534022 (Accessed: 3 January 2025)

Cell Press (2018). ‘What's giant panda conservation worth? Billions every year, study shows’, ScienceDaily, 28 June. Available at: www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/06/180628120114.htm (Accessed: 6 January 2025)

Podcasts and Videos

Cox, M., Wakering, Z. (2022) Art & Ecology Podcast [All Episodes] The Grand Union, Available at: https://open.spotify.com/show/2I8r9uXTLNhXoa6ogf1xu1?si=ee809dfbe7eb4fd4

Hadow, P. (2024) Great Lives [Pen Hadow nominates Sir Peter Scott]. 30 December. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m00269c8 (Accessed: 6 January 2025).

Leave Curious (2024) How Wolves Will Restore Britain’s Rivers. 21 October. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E536f5VRVdg&t=873s

Mossy Earth (2022) Iceland’s Deserts Are Turning Purple – here’s why. 25 August. Available at: https://youtu.be/pQ-dSxYonog?si=qVO2h03On-GCJ_4i

National Geographic (2024) Wolves of Yellowstone. 10 May. Available at: https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/wolves-yellowstone/

Rubin Museum of Himilayan Art, interview with Greenfield-Sanders

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pd4weUkZWiQ

Reviews

Kuspit, D. (2006) Review of Isca Greenfield-Sanders, ARTFORUM. Available at: https://iscags.com/artforum/ (Accessed: 6 January 2025)

Galerie Klüser (2023) Review of Isca Greenfield-Sanders. Available at: https://www.galerieklueser.com/en/artists/isca-greenfield-sanders/ (Accessed: 6 January 2025)

Sarkissian, R. (2024) Review of Isca Greenfield-Sanders: Wildflower Path, 3 July. Available at: https://www.raphysarkissian.com/isca-greenfieldsanders-miles-mcenery-2024 (Accessed: 6 January 2025)

Magagnoli, M. (2011) ‘Critical Nostalgia in the Art of Joachim Koester’, Oxford Art Journal, 34(1), pp. 97-121. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/kcr012

Review of work by Agnes Arnold Forster: -REVIEWS OF BOOK

Hughes, K. (2024) ‘Nostalgia: A History of a Dangerous Emotion by Agnes Arnold-Forster review – no place like home’, The Guardian, 11 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/apr/11/nostalgia-a-history-of-a-dangerous-emotion-by-agnes-arnold-forster-review-no-place-like-home

Reisz, M. (2024) ‘Nostalgia: A History of a Dangerous Emotion by Agnes Arnold-Forster review – the past isn’t a foreign place’, The Guardian, 21 May. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/article/2024/may/21/nostalgia-a-history-of-a-dangerous-emotion-by-agnes-arnold-foster-review-the-past-isnt-a-foreign-place

Websites

WWF (2023) The Panda Icon. Available at https://wwfbrand.panda.org/the-panda-icon/

Brockie, B. (2007) 'Introduced animal pests - Rats and mice', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Available at: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/introduced-animal-pests/page-3 (Accessed: 9 January 2025)

Thank you for reading, I hope you enjoyed

Add comment

Comments